Brandon Sanderson on Building a Fantasy Empire, Wheel of Time ... - Esquire

"This is my dream," Brandon Sanderson says.

We're 30 feet beneath the surface of northern Utah, in a room that feels like a cross between a five-star hotel lobby and a Bond villain's secret base. My ears popped on the way down. Sanderson points to the grand piano, the shelves filled with ammonite fossils, the high walls covered in wood and damask paneling, and his pièce de résistance: a cylindrical aquarium swirling with saltwater fish.

"George R. R. Martin bought an old movie theater. Jim Butcher bought a LARPing castle," he says. "I built an underground supervillain lair."

This is where Sanderson writes bestselling fantasy and science fiction novels. Many of them take place in an interconnected series of worlds called the Cosmere, his ink-and-paper equivalent of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. But instead of superheroes defending Earth, Sanderson's warriors, thieves, scholars, and royals are spread across a richly detailed system of planets, from the ash-covered cities of Scadrial to the shattered plains of Roshar—a landscape directly inspired by the sandstone buttes and slot canyons of southeastern Utah.

It all started 25 years ago when Sanderson, a practicing Mormon, was an undergraduate student at Brigham Young University just 15 miles away in Provo. He took a part-time job working night shifts at the front desk of a nearby hotel, where he could write between midnight and 5:00 AM.

Over the next five years, while working at the hotel during and after his undergraduate years at BYU, he wrote 12 full-length novels that were all rejected by publishers. But one day in 2003, Moshe Feder, an editor at the Tor Books subsidiary of the publishing house Macmillan, discovered one of his manuscripts in the slush pile—and the fate of the Cosmere was sealed.

First came Elantris, Sanderson's 2005 debut about a dead city of immortals once worshiped as gods. Next was the Mistborn franchise, where magic-wielding thieves take down a dystopian empire. Then, in 2009, the wife of fantasy legend Robert Jordan picked Sanderson to finish writing the Wheel of Time series after her husband's death from a rare blood disease. And finally, we've arrived at Sanderson's magnum-opus-in-progress, the dense and wondrous Stormlight Archive, a sprawling ten-volume war epic that reads like The Iliad from another solar system. The fourth and most recent Stormlight book, Rhythm of War, was published in November 2020, with a fifth entry scheduled for November 2024.

Now 47 years old, Sanderson has already published 21 Cosmere books, and he plans on publishing at least 19 more. "But I do have to finish all this by the time I'm 70," he says. I get the feeling he doesn't want to wind up like a certain someone in New Mexico who's already 74. Still, even now, Sanderson is easily one of the most successful and prolific fantasy writers of the century so far.

As we ascend a marble tunnel connecting his underground lair to his home, Sanderson narrates a series of stained glass windows designed by the Chinese Australian artist Jian Guo, each depicting scenes from the Cosmere, The Wheel of Time, and some of his favorite books. "We needed this tunnel because the driveway above it has to support a fire truck for code, so I figured it would be a perfect art gallery," he says, about as nonchalantly as my dad might talk about getting a new refrigerator from Home Depot.

Sanderson has been extremely popular among fantasy readers for more than a decade, but last year, he made international headlines for raising $41 million on Kickstarter (doubling the previous fundraising record) to self-publish four secret books and deliver them directly to 185,341 fans. No publisher, no Amazon, no bookstores.

"I think some of the things [traditional publishing companies] do in New York are wrong-headed," he says. "Somebody has to step up and say, 'Here's another way.'"

Sanderson's wearing his trademark outfit: black loafers, dark jeans, a patterned blazer, and a custom graphic t-shirt made by his team. He says they all come down here to watch movies in the attached 28-seat theater with a sound system so powerful, I could feel it in my sternum.

"I tried for years to get New York publishers to do things differently, and they just weren't willing to. So I'm doing it my way, and if it works, I'll show them it works," he says. "And if it doesn't, I'll fall on my face."

If he's going to change the way books are published in the United States, Sanderson knows he can't do it alone. "George R. R. Martin has two assistants, and so did Robert Jordan. That's normal for writers at the top of their field," he says. Then he turns to his wife Emily, COO of the company they formed shortly after getting married in 2007, and smiles.

"We have 64 people."

From the back seat of a Tesla Model 3, I can see individual fir trees on the Wasatch Mountains, a white palisade of late winter ice and snow that blocks out the eastern sky. We're driving down State Street in American Fork, Utah, a leafy suburb some thirty miles south of Salt Lake City.

We pass through a dense grid of grassy lawns, midcentury ranches, and Mormon temples. Scenes from Footloose and The Sandlot were filmed here, along with last year's Under the Banner of Heaven, Hulu's true crime series about a pair of grisly murders perpetrated by Mormon fundamentalists in 1984, just two miles behind me. It's also where the Sandersons and their company have remained headquartered since buying property in a gated community 15 years ago.

"Some of us are literally family," says Becky Wilson from the passenger seat. She's Sanderson's executive coordinator as well as his sister-in-law. "And other employees are friends from a long time ago."

"I didn't know anyone until I got here," says the driver, Octavia Escamilla Spiker, the company's social media and publicity coordinator. "I'm just a member of the Harry Potter generation, and I love fantasy." Like many people on the team, she's a graduate of BYU, where Sanderson still finds time to teach creative writing as an adjunct professor.

After passing auto repair shops and a tractor dealership, I spot a sign by the side of the road with a familiar logo for Dragonsteel Entertainment, the fast-growing LLC the Sandersons named after a precious metal in the Cosmere. We pull into the parking lot, where Wilson and Spiker escort me into a tall building between a bike shop and a beauty salon.

"This is the warehouse," Wilson says. Inside, there's a front office filled with crocheted creatures from Sanderson's books, alongside gifts from fans. Some of his communications and events staff work here year-round; during my March visit, they're already planning the 2023 Dragonsteel Convention at the Salt Palace Convention Center in downtown Salt Lake City, a two-day series of fan events on November 21 and 22 that culminates with the midnight release of Defiant, the final book in Sanderson's non-Cosmere young adult franchise called the Cytoverse. "We're capping it at 6,000 people," Spiker says, though she expects the 2024 event will have a higher capacity, as it will coincide with the release of the next Stormlight Archive novel.

In the back of the warehouse, a cluster of cubicles for the fulfillment team gives way to an open space the size of a small airplane hangar, where thousands of books and subscription boxes are stacked two stories high in 15 storage bays. We've reached the beating heart of Dragonsteel Books, the publishing and merchandising divisions of Sanderson's business empire.

"To fulfill the Kickstarter, we had to double our staff," Sanderson says. "Most of my [traditionally published] books are sold through Amazon, and I have huge problems with Amazon. They don't treat their employees very well. But if we do it ourselves, we know that people will be treated well, and that helps me sleep at night."

All of the swag and apparel in Dragonsteel's online store gets packed and shipped here, plus exclusive leatherbound editions of Sanderson's previous books and the four new Kickstarter titles and rewards. "We make a long assembly line here on the kitting floor, where we have empty subscription boxes on one end, all the merchandise in the middle, and finished pallets at the other end," says Ally Reep, a fulfillment assistant who joined the team last year to help manage the Kickstarter rewards: eight "themed swag boxes" with exclusive Cosmere and Cytoverse merchandise.

Right now, Dragonsteel's warehouse clerks are packing March's swag box for more than 38,000 backers, including t-shirts, mousepads, stickers, and collectible pins. Soon, they'll be shipping Sanderson's second secret book, The Frugal Wizard's Handbook for Surviving Medieval England.

The first secret book, Tress of the Emerald Sea—a fairytale romance set in the Cosmere and inspired by The Princess Bride—already started shipping to backers earlier this year as a premium hardcover detailed in green leather and gold foil. Like the maps that have accompanied Sanderson's novels for decades, this edition was designed in-house at Dragonsteel by Isaac Stewart. On April 4, Tor Books is releasing a more traditional (but still gorgeous) hardcover with a paper dust jacket available in bookstores and online.

"My New York publishers do good work, but you get an art director who has to put out 350 books a year, and their profit margins are too tight to make books like this," Sanderson says, pointing to his team's luxurious version of Tress. "One thing I think publishing is poorly equipped to deal with right now is letting people pick their price point. "

For years, he tried convincing the former president of Macmillan, John Sargent, to publish multiple editions at different price points—including leatherbound hardcovers filled with original art like Tress and the Emerald Sea—and bundle them with e-books and merchandise. But Sargent never budged. Instead, publishers like Macmillan sell hardcovers and e-books as two separate products—plus paperbacks that hit the market months later, if the titles sell well enough. Sanderson says this punishes readers who choose to spend money to support the authors they love, even though they could pirate digital books or check out free hardcover copies from a library.

"They won't say it, but publishers get really excited by the idea that we can get super-fans to buy three copies of the same book," Sanderson says. "But wouldn't super-fans be happier if they could buy one really nice edition in all formats? Give them a bundle with the print book and the e-book. Reader-centric ideals will lead to long-term success for the publishing industry."

That's why Sanderson turned Dragonsteel into an independent press and started publishing his own books. "The Kickstarter didn't make us more money than just selling those books in New York would have," he says, because of the overhead costs of fulfillment. "But the statement? That's exciting."

I start to wonder if he'll stop working with traditional publishers completely, but for now, Sanderson says his ongoing franchises like The Stormlight Archive and Mistborn will continue to be published by Tor Books, while his young adult line will stay with Delacorte Press, an imprint at Penguin Random House. "I like my publishers. They do good work," he says. "My whole team's well is going to be dry at the end of the year, because this [Kickstarter] is pushing the limits of what we can do." He does have future crowdfunding campaigns in mind, however: "We want to do the Stormlight leatherbound editions as Kickstarters because we like offering goodies and rewards. And I want to do a Hoid storybook collection at some point," he says, referring to a fan-favorite character who hops between worlds (and books) in the Cosmere.

But not everyone was thrilled by the runaway success of Sanderson's record-breaking Kickstarter in 2022. "Today is a really good day to support your favorite author who hasn't made $18M in the last few days," tweeted Natania Barron, a fantasy novelist based in North Carolina. "Am I personally upset at Brandon Sanderson for making money? Not at all. Truly, good for him… If you love fantasy and want to support the genre, I highly recommend reading more & more broadly," she continued, sharing a "starter pack" of diverse writers in the genre, including N.K. Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, and C.L. Polk. Barron's tweet got more than 1,000 likes.

Still, Sanderson paid it forward by donating some of his Kickstarter proceeds to almost every other publishing project on the platform last year, so I ask if he was surprised by all the criticism. "I wasn't surprised. When you're at the top of your field, you're a lightning rod for criticism, and that's actually healthy. The industry needs that. We don't need people criticizing the person just starting out. This is where the criticism should go," he says, pointing to himself.

Sanderson is also the first to admit his biggest regret about the Kickstarter is that independent bookstores were left out. While the traditionally published versions of his secret books will still be distributed by Macmillan in brick-and-mortar stores, hundreds of thousands of backers will already have their Dragonsteel editions by the time Macmillan's editions hit shelves (and even among those backers, there's been some dissatisfaction, as fulfillment has been slow and uneven). Had the books been traditionally published, a percentage of those backers would have bought copies from bookstores instead.

Rebecca George, co-owner of Volumes Bookcafe in Chicago, hosted a huge offsite event at the city's largest library for Sanderson during his 2016 tour for Arcanum Unbounded, a short story collection set in the Cosmere. "He was extremely nice," George says. "A few years later, he even emailed me to apologize when his publisher scheduled an event at a different local bookstore." But George is disappointed that Sanderson's Kickstarter skipped over bookstores, especially given their economic challenges in the long shadow of Amazon. "It's tough," she says. "It makes you wonder if he's forgotten about the people who helped him get here, the booksellers who hand-sold his work for years."

Some critics of Sanderson's Kickstarter campaign also expressed concerns that backing the project was tantamount to proxy-donating to the Mormon Church, whose members are known to tithe, and which, like many religious traditions, has a complicated history with LGBTQ rights, to say the least. Today, a page on the Church's official website states: "The experience of same-sex attraction is a complex reality for many people. The attraction itself is not a sin, but acting on it is." Back in 2008, Church leaders publicly urged their members to vote for California's Proposition 8 referendum to restrict marriage to heterosexual couples; then the Church did a complete 180 by declaring their support for the Respect for Marriage Act in 2022, while still "publicly reaffirm[ing] our Church doctrine approving only marriage between one man and one woman."

In addition to practicing his faith, Sanderson serves as a gospel doctrine teacher at a church near his home. He also teaches a creative writing course at BYU, which is still sponsored by the Mormon Church. In an old blog post from 2007 (which has since been deleted from his website), Sanderson wrote that "impulses of attraction between people of the same gender are something that can and should be resisted," as well as, "I also accept my church's stance against gay marriage."

However, his more recent books feature canonically gay characters, and he seems to have changed his perspective in the years since that deleted post. In response to a Reddit AMA last year, he wrote: "So the church's general stance on LGBTQ people is not where I, as a liberal member of the church, would like it to be… If you look through my own history with LGBTQ people, I needed some education as many did. (I still do, honestly.)... My belief is that, by being a more liberal member of the church and remaining with the church and remaining at BYU, this is a way of getting to where we want to be." And in another Reddit response earlier this year, he elaborated: "I always get a lump in my stomach when I see someone has dredged up that essay. But at the same time, I'm glad I wrote it, since without it, I don't think I'd have had the opportunities to learn that I have."

Later, I ask Wilson if Dragonsteel tithes or donates revenue from the Kickstarter or other online sales to the Church. "In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, tithing and other charitable offerings are considered personal religious commitments," she says. "Dragonsteel as a business does not donate any of its revenue to the Church, although individual Dragonsteel employees who are members of the Church may choose to contribute from their personal earnings at their discretion."

Of course, tithing isn't a Mormon phenomenon; it's extremely common among many religious faiths around the world, including people who identify as Protestant, Evangelical, Catholic, Muslim, and Jewish. But according to a 2012 Pew survey, 79% of American Mormons tithe 10% of their earnings, a much higher percentage of members than you'll find in similar surveys of other religious groups.

"Tithing is a principle of my church that I believe in," Sanderson tells me. "So is giving to those who need, and to causes I believe in. However, Jesus Christ taught us not to speak loudly about our charitable giving—indeed, he made it very clear that we are to do the opposite. I generally try to follow this by saying that yes, I do give to my church of my personal funds. I also give to many other causes. The actual numbers and amounts are, generally, private."

But another Sanderson critic emerged just a few hours before this story was originally scheduled to go live: Jason Kehe, a senior editor at WIRED magazine, who spent even more time in Sanderson's orbit than I did. In his viral profile, "Brandon Sanderson Is Your God," Kehe criticized Sanderson's prose, reputation, clothing, eating habits, state of residence, faith, fans, friends, and family for being—among other adjectives—"depressingly, story-killingly lame."

Unsurprisingly, a legion of fans came to Sanderson's defense on social media, but some neutral parties were confused by Kehe's oddly hostile language. "I've never read Brandon Sanderson but this profile of him feels outrageously almost egregiously mean for no reason," wrote Dana Schwartz, author of Anatomy, A Love Story and host of the Noble Blood podcast, while the journalist Katy Kelleher came up with a possible explanation: "I think the writer of this realized, after hours of interviews, that he wasn't properly recording." Other people enjoyed the profile, including Peter Rubin, Head of Publishing at Automattic, who picked the story as one of the "top five longreads of the week."

Later that same day, Sanderson shared a lengthy response on Reddit and Twitter, thanking his fans for their support but asking them to leave Kehe alone. "I respect him for trying his best to write what he obviously found a difficult article," Sanderson wrote.

Over the phone a few days later, Sanderson tells me he felt a lot of different emotions when he sat down to read the story. "I felt betrayed. That was the strongest feeling I had after spending so much time talking to him about things he seemed so interested in," Sanderson says. "But I respect [Kehe] as a colleague. He's a writer, so he has to write what's true for him, just like you do, and just like I do."

Sanderson tells me he hasn't heard from Kehe or anyone else at WIRED since the profile ran. "But I hope I can talk to [Kehe] again at some point," he says. "Anytime I get criticism from anyone, my job is to listen." Before we hang up, he compares this experience to something in the Cosmere. "One of the main themes of Mistborn is that it's worth trusting people, even though they can hurt you," he says. "It's better to trust and be betrayed in real life, too."

Over email, I ask Kehe a few questions as well. Why did he read so many of Sanderson's books if he didn't like the writing? Was he surprised by the responses to his story? Did the responses change his perspective on anything? Kehe writes back: "As I've said to others, the piece belongs to readers now. They get the last word."

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Back in Utah, right before we leave the Dragonsteel warehouse, Reep shows me a wall of life-sized rubber and plastic swords from the Cosmere. Wilson picks up Szeth's honorblade from The Stormlight Archive and I wonder if we're about to duel, but she loses her grip and drops it on the floor. The opportunity has passed.

As a reporter, I've interviewed staff members at corporate offices who are desperate to show off their company culture. Sometimes their smiles look a little painful, and every few minutes they check their phones for urgent emails and Slack messages.

Dragonsteel doesn't feel like that. The employees here are comfortable with one another, genuinely laughing at frequent jokes. They seem driven and passionate about their jobs—and about the Cosmere as a playground for their imaginations. Several people I met were writing or publishing their own novels, inspired by the worldbuilding they do every day at work, and one of the warehouse employees, Mem Grange, has made a side career out of crochet patterns for Cosmere fauna.

Walking back to the car with Wilson and Spiker, I remember something Sanderson said underground: "All I can say is, I want to do cool things [that] make the industry better for everybody. And I'm trying my best to do them in a morally upright way while treating people well."

The above-ground portions of Sanderson's home are more modest than the subterranean wing. In the early 2010s, he and Emily bought a two-story house and the empty lot just south of it for a little over half a million dollars, according to public records. A few years later, they purchased the home next door.

Today, that second home is office space for Dragonsteel's editorial, design, and production staff. "We call it the Cosmere House," Wilson says as we step onto the porch. Each room is themed after one of Sanderson's books, from the wall coverings to the furniture and knick-knacks.

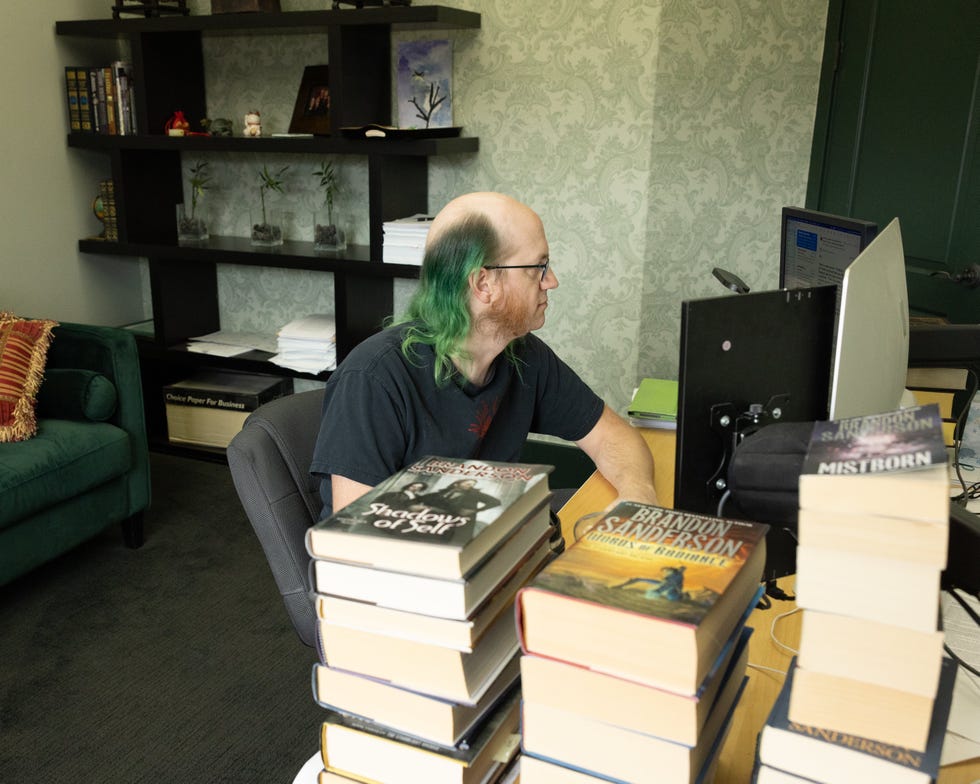

We meet the barefoot Peter Ahlstrom, Vice President of Editorial, who's writing cover copy for Tor's forthcoming edition of The Frugal Wizard's Handbook. "I was Brandon's first full-time employee," he says, back when all Sanderson needed was "an extra brain." Now he's the in-house copyeditor and proofreader for the hundreds of thousands of words Sanderson cranks out every year.

"Brandon doesn't like doing the later stages of editing, but I love it," Ahlstrom says. "And my wife Karen is the continuity director, so she keeps our internal wiki with hundreds of characters and locations." Some of those characters are thinly disguised cameos from Sanderson's staff, including "Peet" and "Ka" in The Stormlight Archive—the Ahlstroms' alter egos.

In the unfinished White Sand room, we meet Dan Wells, Sanderson's co-host on the Intentionally Blank podcast, who's in the middle of playtesting a Cosmere role-playing game. "I'm the vice president of narrative, which basically just means that I write books and stories," he says, referring to some top-secret future projects, including collaborations with Sanderson.

Upstairs, the art department is working on the detailed paintings, drawings, and other visuals that make Sanderson's books so unique. Down in the basement, we pass another half-dozen desks on our way to the streaming studio where Sanderson records two podcasts, Intentionally Blank and Writing Excuses, as well as weekly update videos for his YouTube channel.

Sanderson and his wife take seats across the table from me while Wilson brings everyone a Coke Zero. I ask a question I've been thinking about since I arrived: "Where do you find the energy to do all of this? Writing two books a year, teaching, podcasting, and running a business, not to mention parenting three kids. I've only got two kids, and I'll be lucky if I file this story on time."

Sanderson laughs. "The part of my job I spend the most time doing is the energizing part. I legitimately love writing books. It engages my mind in a way that no other activity does, and because of that, energy is not a problem."

Some of his energy, which you can almost see radiating off his shoulders if you spend more than five minutes with him, might be explained by his working schedule. Sanderson sleeps until one in the afternoon most weekdays, writes from two to six in the evening, takes a long break to spend time with his family, then writes for another block between 10 p.m. and two in the morning. After that, he's free to spend two hours doing whatever he likes before going to bed.

Last year, he spent a lot of those "discretionary hours" playing Elden Ring with what he calls a "glass cannon build"—two colossal swords, no shield, no spirit ashes, and very light armor. "And no pants," his wife adds. Sanderson nods: "I started as the wretch with no clothes on, and I got all the way through the first boss before I found pants." It took him 14 hours to beat Malenia. "She's the toughest boss I've ever fought."

In some ways, Sanderson thinks the video game industry is light-years ahead of book publishing. "They let you self-select your price point by getting these really cool items," he says. Elden Ring, for instance, retailed for around $60, but consumers could spend a little more for a deluxe edition with a digital artbook and a digital soundtrack, or four times as much for a collector's edition with a nine-inch statue of Malenia.

That's when I realize that the Cosmere House, more than anything else, feels like a mid-sized indie game studio. Sanderson's vision of his fictional universe—the level of detail he wants in order for it to feel real—is just too big for one person. So like a video game developer or a filmmaker in charge of a massive franchise, he's hired artists and writers and production experts to help bring his worlds to life. And the most remarkable thing is, he's just getting started.

"We would love to build a bookstore [and a real office]. We're exploring that possibility. It would be very easy to overspend on something like this and crash the whole company. But we also can't keep having everyone work at the warehouse and here," Sanderson says, gesturing to the Cosmere house.

In fact, Dragonsteel has already found a new warehouse a short drive away from their current one. "It's literally 10 times the size of the warehouse we have now," Wilson says. She shows me a massive floor plan with room for 600 pallets and far more office space for the fulfillment team and other staff. Dragonsteel also purchased a large parcel of property across the street from the new warehouse, where they'll eventually build the bookstore-slash-office called Dragonsteel Village.

"We'll see if our philosophy holds out, but the idea is that you invest in your people and the company will be successful, rather than investing in your company first," says Sanderson's wife, Emily.

Back when they first founded the company, Emily quickly became Sanderson's business manager, "helping with fan mail and doing all the paperwork." But as her responsibilities grew, she hired more and more people to help. Now, she acts as the COO for a one-of-a-kind business: part independent press, part merchandise manufacturer, part streaming content producer, part editorial and artistic support system for the Cosmere.

"Brandon's the big vision person and I'm the detail person. I probably wouldn't dare do some of this on my own," she says.

"And I'm a little overambitious," Sanderson adds.

After the Kickstarter books, the next major milestone for the Cosmere is the fifth Stormlight Archive novel, tentatively titled Knights of Wind and Truth. It's the halfway point of the series, so the stakes are high. "In-world, it'll be a ten to 15-year gap between the end of book five and the beginning of book six. In the real world, the gap between books will be double what it usually is, so six years instead of three," Sanderson says.

During that gap, he wants to write a third trilogy set in the Mistborn universe. Before he retires at 70, he plans to write five more Stormlight Archive volumes, a fourth Mistborn trilogy, two sequels to Elantris, and a trilogy called Dragonsteel about the origins of the Cosmere. He has ideas for more books, too.

"I know exactly how The Stormlight Archive ends," he says. "I've been very sneaky with some of the foreshadowing in ways I can't tell you about, because then people will figure it out. The end of the Cosmere is a little more vague, but I know what I want to do."

Some fans have theorized that elements of the Cosmere were directly inspired by Sanderson's faith. For example, the three main planets in The Stormlight Archive share some similarities with the celestial, terrestrial, and telestial kingdoms in Mormon cosmology.

"I think the interpretations that fans make are most likely valid, but I don't do it consciously," he says. "Tolkien abhorred allegory, and C.S. Lewis really leaned into it. I'm totally fine with allegory, but I'm more like Tolkien. I don't write books to teach lessons, I write books to be uplifting in people's lives."

Before I lose Sanderson to a podcast recording session, I ask whether he thinks Dragonsteel will change the book publishing industry for the better.

"If I can get some other authors on board to push for some of the same things, yes," he says. "My biggest worry is that I'm just one person."

That much is true. Sanderson is just one person, and so far, major publishers don't seem interested in changing their sales and production models.

But sitting in the basement of the Cosmere House—surrounded by hundreds of books, original paintings, replica swords, and the largest team a novelist has hired since Johannes Gutenberg put a bunch of metal letters on a block of wood in the 15th century—I can't help but wonder if Dragonsteel's unprecedented success might turn a few influential heads in New York when it comes to price point flexibility, or e-book and merchandise bundling.

One of the last things Sanderson says is, "I want this to be the best place to work that a person could have," and I remember one of the warehouse employees I met earlier, Kaleigh Arnold, a fulfillment clerk who joined the team last year during the Kickstarter boom.

"This is one of the best places I've ever worked," she said with a genuine smile.

I think she meant it.

Comments

Post a Comment